Szállítás:

5-15 munkanap

Rendelhető

4 591 Ft

Eredeti ár:

4 990.-

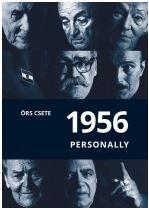

My father, a student at the Budapest University of Technology in 1956, took photos all over the revolutionary capital; my mother, a secondary school student at that time, remembers the Soviet tanks from the beginning of November. I was born 10 years later; I was in school in the years of the vast human experiment called socialism.

Leírás

My father, a student at the Budapest University of Technology in 1956, took photos all over the revolutionary capital; my mother, a secondary school student at that time, remembers the Soviet tanks from the beginning of November. I was born 10 years later; I was in school in the years of the vast human experiment called socialism. In school, the events of the autumn of 56 were taught as counter-revolution, but it was best not to talk about them at all. Generations grew up that way, one after the other, socialized to silence. The change of the regime in 1989 brought a radical change in the judgement of the Revolution: the terminology changed, archives were opened, participants, eyewitnesses started to speak. Faces and stories of the Revolution emerged. I met some former armed fighters for the first time in 1993. I recorded our conversation during the photo shoots; that was how this album came into being. Having talked to one and a half hundred former participants, based on their lifestories, I think that in most cases decisions are not made in 2-bit systems, they cannot be reduced to black or white, but rather they are made up of lots of shades and motives. People are heroes in one moment of their lives, and feeble in another. My portrait subjects behaved as heroes at least in one moment of their lives: when they stood by the Revolution, when they behaved bravely, when they helped the refugees, when they didnt present a petition for pardon. Although the Revolution has no museum in Budapest yet, these people deserve their faces, stories and names to be preserved at least on the pages of this book, and also on the internet, on the website of the 24th Hour Project I edit (www.1956.hu). The Hungarian and foreign portraits revive the participants of the Revolution and the helpers of the Hungarians. It is not my aim for the interviews to be representative, or to convey exact historical knowledge, as there is plenty of literature available for those interested. My portrait gallery of 111 people commemorates thousands who chose freedom in 1956, those who went to the streets, who grabbed weapons, who stood by the Hungarian nation or by one single Hungarian abroad. Next to the Italians, Poles, Finns, Romanians and Austrians presented here, people of other nations are still missing from these pages. I keep on searching for and meeting Hungarian participants and our foreign friends who are still alive. I hope that the everyday greatness of the struggle for freedom and human solidarity appear genuinely on the pages of this book. Örs Csete

Adatok

Raktári kód:

L21056

ISBN:

9789633022085

EAN:

9789633022085

Megjelenés:

2017.

Hozzászólások